The old masters' glazing technique involves applying multiple layers of transparent paint over a dry base color to achieve depth, richness, and subtlety in color variation. This method allows for the creation of luminous tones and intricate details, characteristic of many historic paintings.

Unlocking the Lost Secrets of the Old Masters: The Evolution of Binding Medium in Oil Painting

The separation of artists from their craft became widespread in the nineteenth century, but it was a trend that had begun much earlier. By the early seventeenth century, the dominance of architects over masons and carpenters in the building trade was established. At about the same time, the status of painters began to rise.

This separation may have been encouraged by or perhaps even inspired the industrialization of artists’ materials, but it also had far-reaching effects on the materials and practice of painting. Materials began to be used capriciously, and construction became less important than effect. Whereas the whimsical use of materials may have always existed among painters, it was always guided by the traditions of the workshop. For the first time, artists yielded a power formerly the domain of the evolutionary process of craftsmanship.

Establishment of the Academies and the Change in Art Education

The rise in the status of artists was aided by the establishment of academies which evoked changes in the education of young painters. One of the earliest academies for painting and sculpture was the Accademia di San Luca founded as an association of artists in Rome. Earlier academies, such as the Compagnia di San Luca, were guilds of painters. Differing markedly from that of its predecessor, this Academy's purpose was to elevate the work of artists, which included painters, sculptors, and architects, above that of mere artisans.

The Accademia di San Luca later served as the model for the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, founded in France in 1648 to distinguish artists “who were gentlemen practicing a liberal art” from craftsmen, who were engaged in manual labor.

One fact should be clearly understood: the Paris academy was never meant to deal with the whole of the professional education of a young painter or sculptor. He neither painted nor carved nor modeled figures or reliefs during his working hours at the academy. All this he had to learn in the workshop of his master, with whom he still lived and under whom he still worked, in a way almost identical to that of the Middle Ages.

Academies based on the French model formed throughout Europe and imitated the teachings and styles of the French Academy. In England, this was the Royal Academy of Arts, founded on December 10, 1768. The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1754, may be taken as a successful example in a smaller country, which achieved its aim of producing a national school and reducing reliance on imported artists.

However, as the emphasis on the education of young artists changed from a traditional craft in workshops to one of the liberal arts taught at academies, the status of artists was simultaneously elevated. Whether or not this change in status had an effect outside the sphere of artists, a growing number of individuals began practicing the art of painting for pleasure, creating a new class of painters, amateur artists. This new class of painters created a distinction from artists trained in the workshops where a certain minimum standard of quality was expected. There was no expectation of training or quality for amateurs who perhaps attended academies but did not work in artists’ workshops.

Loss of Skills from Changes Brought About by Industrialization

The industrialization that began first in England about the middle of the eighteenth century changed how painters worked by freeing them from the labor of making paint. Still, it also released them from the discipline of their craft.

The commercial production of and packaging of paints is central to art history in the nineteenth century. British colormen were at the forefront of developments from the ‘colour-clothlets’ of the medieval limner to the appearance of bladder colors in the seventeenth century, to the watercolor cakes of the Reeves brothers, and the introduction of collapsible metal tubes for oil paints. These innovations were undoubtedly in response to the demand created by professional painters distancing themselves from the manual labor of their craft. Still, another source was the new demand from the growing ranks of amateur painters.

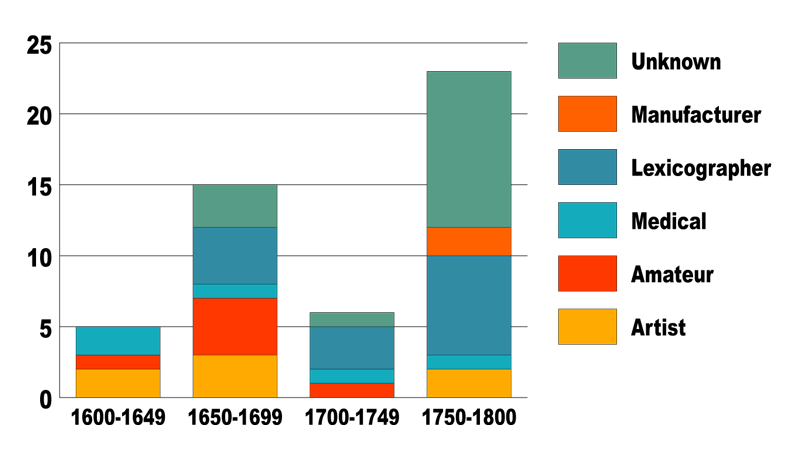

Dutch authors of artists’ manuals from 1600–1800 were divided into categories based on ‘From reading to painting’ Authors and Audiences of Dutch Recipes for Preparatory Layers for Oil Painting by Maartje Stols-Witlox.

That amateurs were a new and growing segment of artists in the seventeenth century is evident from the number of painting manuals written by amateur artists in the second half of the century.

This demand likely developed shops specializing in artists’ materials in the seventeenth century. In his Italian notebook, Richard Symonds, a seventeenth-century amateur painter, describes how shops or ‘botteghe’ sold brushes, canvases, and colors in bladders.1

Much of these materials were still produced by workshop apprentices because professional artists seldom relied on unscrupulous colormen who often adulterated expensive materials with cheap substitutes. That colormen were not always to be trusted is evident from William Williams’ account in his Essay on the Mechanic of Oil Colours of ‘the use of a bad oil procured from a colour shop, the pictures never dry’d... but ran down in tears, whether from the folly of the artist or the knavery of the colour-man history says nought.’ 2

The system of education in the medieval workshop that gave individuals basic painting skills was in decline due to industrialization. Innovations like packaged colors such as watercolor cakes and tubed oil paint furthered the painter’s position by detaching him from the manual labor needed to produce them. Although industrial development created new opportunities for painters, such as plein air painting, it ultimately removed artists from the firsthand experience gained by making these commodities.

The artist’s understanding of his materials, while being superficial and intuitive, was not theoretical. The grinding of pigments and preparation of paints was one of the most labor-intensive aspects of the painter’s workshop. Every workshop had servants whose sole job was to grind pigments and prepare the paint, as seen in the engraving Color Olivi by Johannes Stradanus of 1600. The close association between painters and pigments provided an empirical understanding of materials.

By the late eighteenth century, that situation had changed due to the availability of commercially produced pigments and paints. William Williams, in his Essay on the Mechanic of Oil Colours, refers to this situation by admonishing artists to ‘make himself well acquainted with the qualities and hues of the different pigments in their dry state, that he may judge of the goodness or deficiency of them when ground in oil, it is a pity, but it is true, there are many, and some of much merit, that scarce know the difference of umber and oker in their crude state; seldom if ever seeing them but in bladders.’ 3

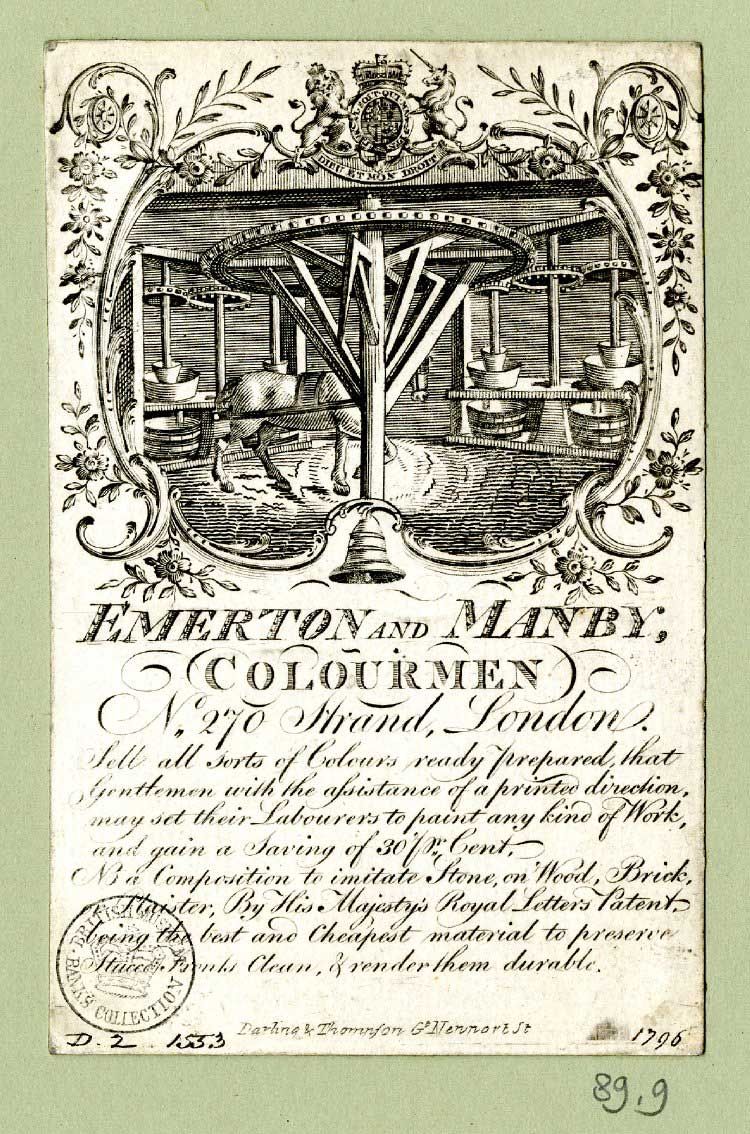

Most of the innovations in artists’ materials occurred first in England. The first references to “bladder colours” are found in English publications of the seventeenth century.4 By the eighteenth century, this method of storing paint was quite common, and numerous colormen advertised ‘bladder colours’ on their trade cards without the need for further explanation.

Of course, even from early times, the basic pigments were obtained from colormen. Making pigments into paint was the sole responsibility of the artist workshop until the seventeenth century.

Only the large-scale production of paints could sustain any degree of mechanization. In 1785, John Morgan announced in the Independent Journal of New York that he had ‘erected a mill for the sole purpose of grinding colours.’ 5 Windmills and water mills became the source of motive power for the making of colors.

A horse-powered mill is illustrated in the trade label of Joseph Emerton, whose son-in-law continued the business from about 1744 to 1753. Turner recorded a mill of this kind in his painting An Artists Colourman’s Workshop of 1807. As seen in the background, horse- and donkey-drawn mills were used for grinding large quantities of cheap pigments, such as ochres, siennas, and umbers, used by decorators and artists. The colorman himself is grinding red pigment into oil, using a heavy muller.

Why the Search for the Lost Secrets Began

The loss of direct experience with pigments and their interaction with binding media and the aspiration of artists to the intellectual and social distinction established by the Academies may explain why artists in the eighteenth century began searching for secrets that would allow them to achieve the glorious colors of the old masters.

This developed into an obsession with many painters working in England toward the end of the eighteenth century. It is as though artists viewed painting mediums as a Philosopher’s Stone, transforming mediocre work into masterpieces. Finding the supposed secrets of the old masters was one reason for the change in binding media. These artists believed that the genius of Titian and the Venetian School could be attributed to using a secret medium.

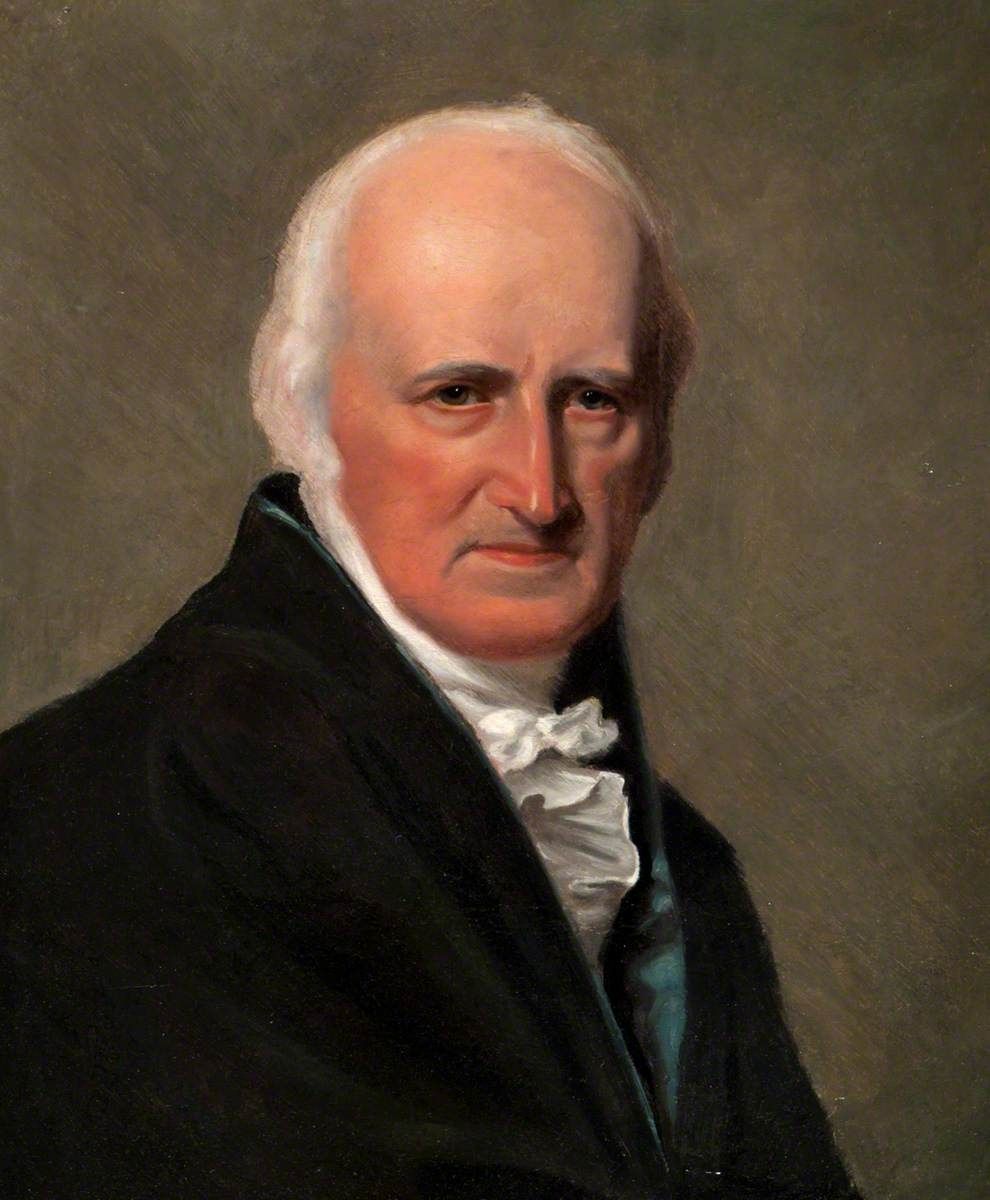

The obsession even led to a scandal for Benjamin West, then president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London. West and several of his colleagues thought the supposed secrets used by Titian and other sixteenth-century Venetian masters were revealed to them.

An artist named Ann Provis and her father, Thomas Provis approached West with what they claimed to be a copy of an old manuscript that explained how the Venetians worked. For ten guineas, one could get a personal demonstration of the techniques described in the manuscript from Ann Provis.

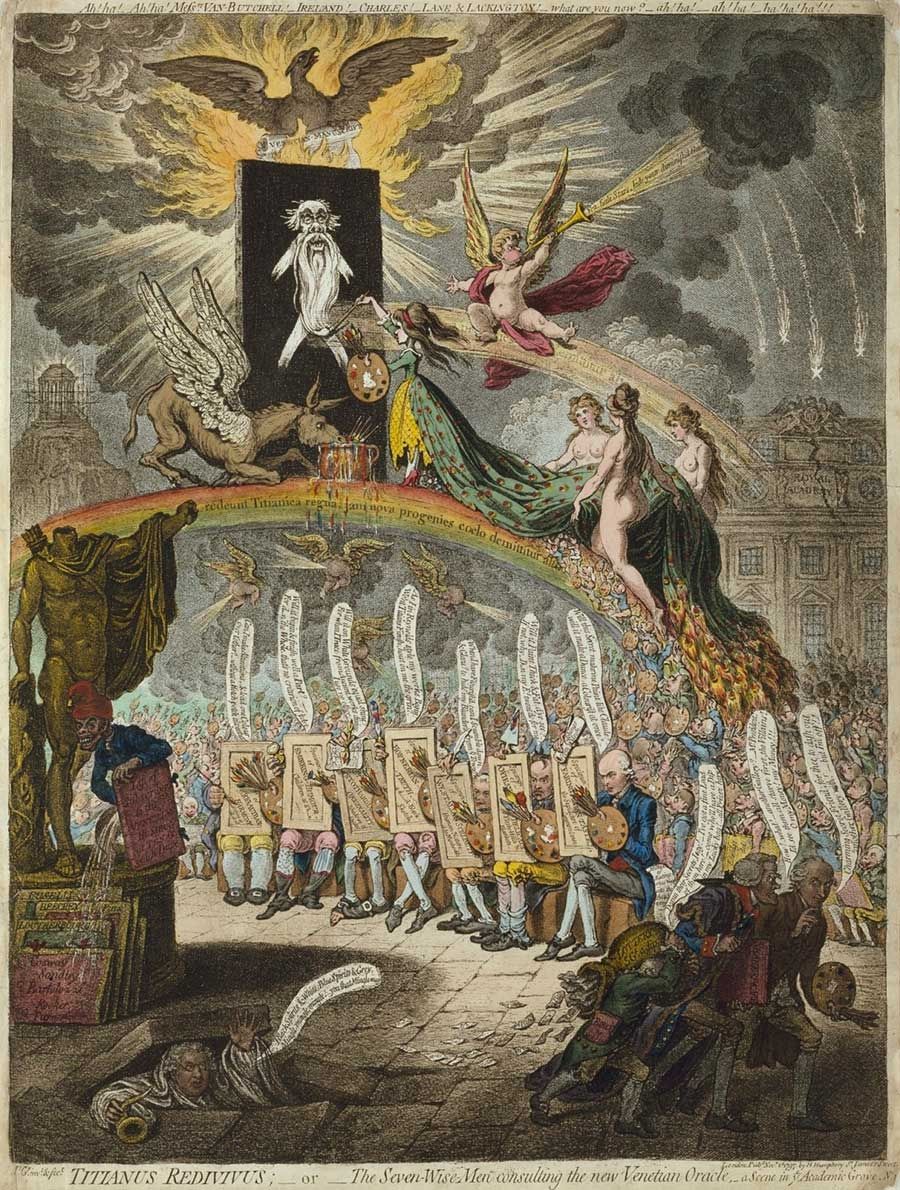

In his eagerness to learn the methods of the Venetian painters, West began using the methods described in the manuscript in his work. The problem was that the manuscript was fake. When the fraud was finally exposed, the embarrassment was far worse for West than for the other victims. West was ridiculed in song, in the press, and a satirical engraving titled Titianus Redivivus by James Gillray.

The whole episode demonstrates the confusion that arose between the practice and theory of art, a confusion for those painters who were trained in the workshop traditions and who now aspired to the social distinction the Royal Academy institutionalized and that Joshua Reynolds’ Discourses provided a manifesto.

Joshua Reynolds’ Capricious Use of Materials

Reynolds is the archetype of artists in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Although one of the greatest artists of his time, many of his paintings suffered defects compared to earlier works due to the absence, in his case, of the artistic tradition on which the others leaned. English painters in their early days possessed a sound technique, and many of their best pictures are well preserved. Reynolds was not content with the methods of his teacher Thomas Hudson. In his desire to achieve the effect he found realized in the works of the Venetians, he embarked on all sorts of fantastic experiments in pigments and media.

The painter, Benjamin Haydon, referring to Reynolds’ use of wax and megilp, said ‘he wondered that Reynolds’ paintings did not crack while still on the easel.’ 6 The result was the ruin of many of his works and the commencement of an era of uncertainty in the method that seriously compromised the efforts of many artists following him. He accounts for his own uncertainty partly from his want of training and partly from his ‘inordinate desire to possess every kind of excellence’7 that he saw in the works of others.

Common to many of his experiments was an oil painting medium called ‘megilp.’ In fact, one of the earliest mentions of this medium is found in Reynolds’ notebook of 1767. This medium consisted of a mixture of mastic gum dissolved in turpentine and mixed with black oil; an oil medium composed of linseed or walnut oil cooked with litharge or white lead. Earlier recipes often omit the mastic and substitute wax.8 The obscure origin of the word ‘megilp’ is reflected in the many variations of its spelling; by 1854, a total of 23 different versions were listed in Fairholt’s Dictionary of Terms in Art.9 The medium makes oil paint thin, glossy, and easy to work with a short drying time. When added to oil colors, it creates glazes that help to produce the sensation of depth by producing transparent colors that hold in place rather than running or sagging.

Reynolds used a variety of formulations and proportions of megilp in his work, which has led to variations of yellowing and solubility in his paintings and made them very sensitive to cleaning. An example of Reynold’s use of megilp can be seen in the portrait of Lord Heathfield of Gibraltar. Examination of paint cross-sections allowed conservators to relate the physical effects visible on the paint surface to the materials chosen by Reynolds and his particular painting methods.

The Result of ‘Lost Secrets’ Painting Media

The portrait of Lord Heathfield, so much admired in its day, has unfortunately suffered from the irreversible effects of Reynold’s painting techniques. A treatise on the art of painting published in London in 1797, only ten years after the picture was painted, cautions against such methods:

“Many Painters, both in Glazing and in Painting, make use of varnish mixed with fat oil, because then the Picture appears brilliant, and not imbibed.”

“This method, so pleasing, and therefore so seducing in practice, may, without doubt, be useful; but then it ought to be used with precaution. To this may be attributed the change that the Pictures of the celebrated Sir Joshua Reynolds have undergone.” 10

A report published in 2010 on the condition of the painting today concludes that the painting should not be cleaned and that the removal of the restorer’s varnish ‘could not have been done safely.’ 11

In addition to megilp, Reynolds used several other binding media and mixtures, such as in the paintings of Sarah Siddons, some pictures painted entirely in wax. In contrast, others combined layers of oils interspersed between complex mixtures of resin, waxes, and oil.

It is clear that Reynold’s use of resinous mediums was responsible for the severe cracking in many of his pictures. One of his pupils, James Northcote, wrote about Reynold’s technique in a letter to his brother dated August 23, 1771:

“He uses his colours with varnishes of his own because the oils give the colours a dirty-yellowness in time, but this method of his has an inconvenience full as bad, which is that his pictures crack; sometimes before he has got them out of his hands.” 12

Northcote also remarked, ‘it is common with painters in London to use mastic varnish with their colours.’

Rediscovering the ‘Lost Secrets’ in the Nineteenth Century and New Binding Media

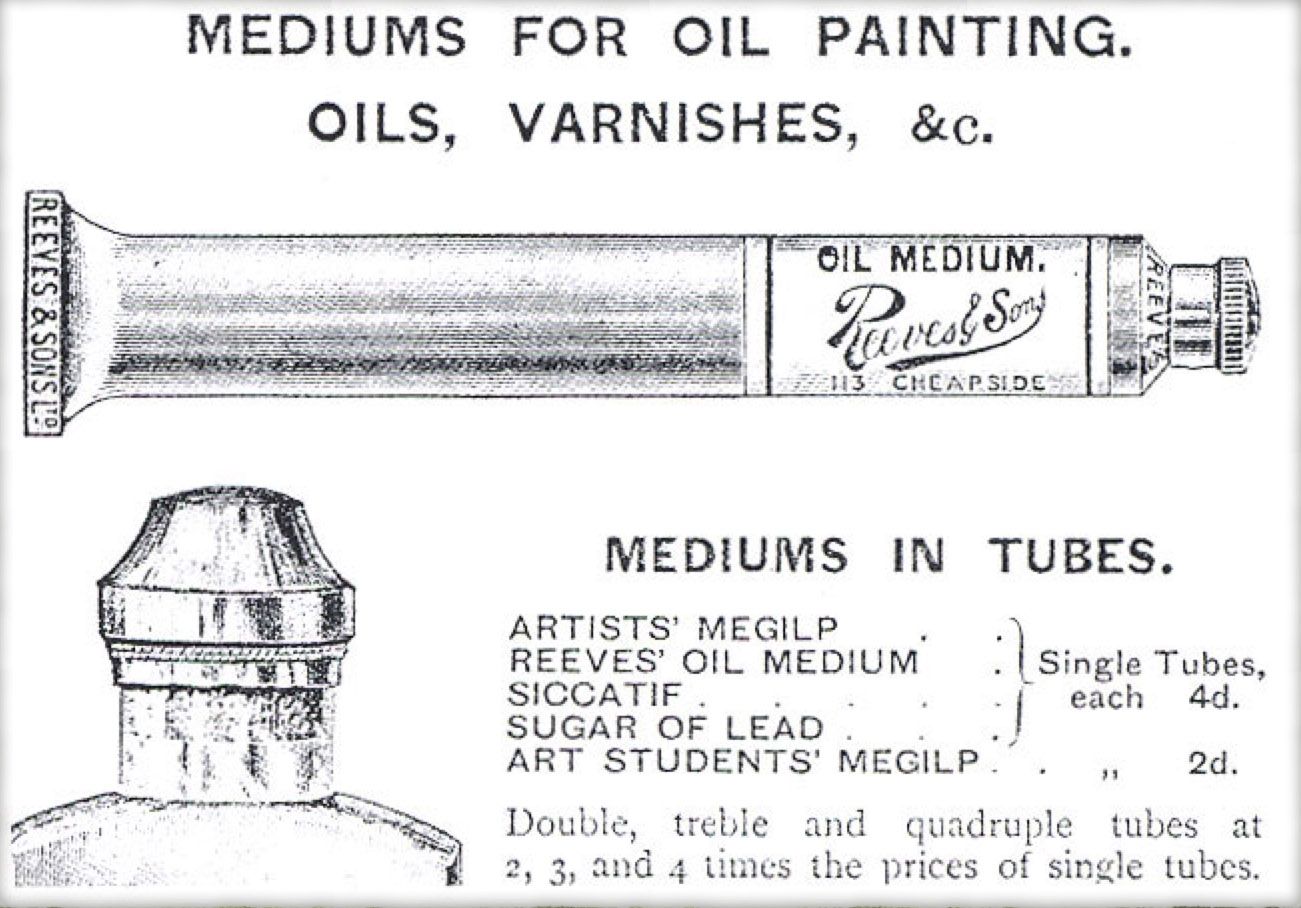

The widespread use of such mediums by artists in the latter half of the eighteenth century led to the commercial production of a multitude of varnishes, such as copal oil and spirit varnishes, and mediums based on such varnishes, such as Roberson’s Medium, which was a mixture of mastic varnish, copal varnish, and black oil.

The use of such complicated applications of paint and the combination of oil and resin, such as megilp, gumption, and copal mediums, which are so characteristic of paintings by artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as this one by Turner, appear to be responsible for many of the drying defects in paintings of this period.

Rediscovering the ‘secrets’ of the old masters prompted more experiments with wax and resinous ingredients. Hard and soft natural resins were extensively used and written about in the growing field of literature on painting technique. The addition of waxes and resins to paint was widely believed to bring greater transparency, durability, and handling properties than oil alone.

Sir Charles Eastlake sought to discover the reasons for the durability of early oil paintings in the hope that his research published in Materials for a History of Oil Painting would help artists of his day. Like many writers of the nineteenth century, he primarily focused on resinous mediums as the key to understanding the technique of early oil painters.

Johann van Eyck’s works were esteemed as the epitome of oil painting in the eighteenth century, especially for Eastlake. As Keeper of the National Gallery in London from 1843 until he published the first volume of his book in 1847, he could examine firsthand the Arnolfini Double Portrait acquired by the museum in 1842. Based on his examination and study of literature, he concluded that resins were the key to the brilliant colors and fine rendering of details in early oil paintings.13

Eastlake argued that amber and copal was the resin used by Van Eyck in his second volume of Materials for a History of Oil Painting. He referred to Timothy Sheldrake’s experiments published in the Transactions of the Society of Arts in 1801, which relate to the attempts by this amateur artist to discover the medium of sixteenth-century Venetian masters. Sheldrake found that paints composed of oil and hard resins were more brilliant and resistant to solvents than pigments ground in oil alone.14

The drawbacks of these vehicles are their tendencies to flow and to yellow. To counter these disadvantages, many recommendations were made by artists and writers, such as the sparing use of resinous mediums, the addition of dryers, and the use of solvents such as turpentine and spike oil.

Eastlake did make some perceptive observations of Van Eyck’s technique. Eastlake stressed the artists’ intimate knowledge of his materials, stating that ‘Instead, therefore, supposing that the first oil painters had achieved impossibilities by inventing a permanently colorless varnish, it may be concluded that they had the sagacity to adapt their processes to their materials.” 15

Eastlake recognized that the brilliance of the paint was produced optically by painting thinly on a bright white background. Yet Eastlake could not give up on the idea of using varnishes in oil paint. He theorized that Van Eyck varied his use of resinous mediums in his work, using amber varnish in dark colors and a ‘white’ varnish in light areas and blue.16

What has since been found is that both linseed and walnut oil were used by Van Eyck and his contemporaries and that both oil and tempera were sometimes combined on the same panel. Van Eyck’s process appears to have been more simple, and analyses of his paintings reveal that he used both bodied and unmodified linseed oil and sometimes pine resin, depending on the drying and optical properties of his pigments.

For the remainder of the nineteenth century, the use of resins in oil paint dominated the literature on painting techniques and continued in popularity among artists, as evidenced by the numerous product offerings in artists’ materials catalogs.

Oil Emulsions as New Binding Media

Interest in complex mediums continued without missing a beat among artists and authors of painting manuals in the twentieth century. Max Doerner, professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was particularly influential in the first half of the century when he argued that Van Eyck used an egg emulsion with an oil varnish that could be thinned with water. His speculations were based on the methods that he and his students used in making copies of the master; when they obtained the effects that they found similar to the originals, they concluded they had stumbled upon the actual material and process used by Van Eyck.

Interest in complex mediums continued without missing a beat among artists and authors of painting manuals in the twentieth century. Max Doerner, professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, was particularly influential in the first half of the century when he argued that Van Eyck used an egg emulsion with an oil varnish that could be thinned with water. His speculations were based on the methods that he and his students used in making copies of the master; when they obtained the effects that they found similar to the originals, they concluded they had stumbled upon the actual material and process used by Van Eyck.

Helmut Ruhemann, a consultant restorer for the National Gallery of London, commented on Doerner’s methods described in his book, The Materials of the Artist and their Use in Painting. He observed that copying is not a reliable way to understand technique because one is forced to simulate the properties of paint acquired through age.17 He went on to note much of the work of Doerner’s students using his method was in poor condition.18

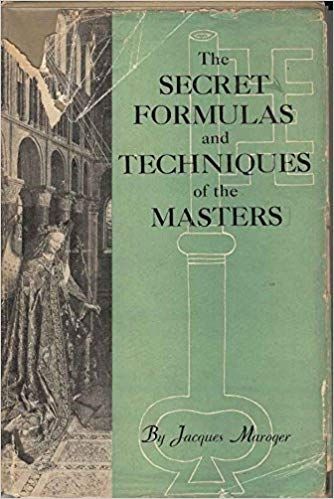

Jacques Maroger had an enormous influence on artists in the twentieth century. Maroger was a painter and conservator at the Louvre before coming to the United States, where he was a professor of the Arts Students League of New York and the Maryland Institute of Art. From its original inception in 1932, his complex formulas of the early masters morphed from an emulsion of bodied linseed oil, calcined bone, litharge, and resin mixed with gum arabic or hide glue to one of dammar and linseed oil whipped with a solution of gum arabic in another emulsion. He also theorized the mediums for later masters, mostly consisting of mastic spirit varnish and ‘black oil’ made with large amounts of litharge.19

One of the most consulted books of the twentieth century is The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques by Ralph Mayer, first published in 1940. Although revised many times since then, the book still propagates the mixed technique by early Netherlandish artists.20 Mayer criticized Maroger for his recipe of black oil and mastic spirit varnish in a review of Maroger’s book in the Magazine of Art.21 He later wrote in The Painter’s Craft, “History teaches us that the wisest course is to adhere to the simple oil-paint technique as much as possible, to use oleoresinous painting mediums with restraint and to avoid complex jelly mediums.” 22

In seeming contradiction to his advice, Mayer recommended his own resinous oil painting medium of one-third dammar varnish, one-third turpentine, and one-third bodied linseed oil. This medium became widely used by artists in the latter half of the century and continues to enjoy popularity today.23

Although conservation research in the twentieth century continues to inform us that the binding medium of masters prior to the eighteenth century consisted mostly of linseed and walnut oil used in simple techniques, the number of painting manuals and treatises on historical painting techniques claiming to have discovered the lost secrets of the old masters has not let up.

As recently as 2004, American Artist magazine proclaimed, “Now Donald C. Fels Jr. has produced evidence of the secrets of the Flemish masters…” “This book is the culmination of 11 years of research with Frank Mason in rediscovering the mediums and methods of painting, which due to the deaths of Van Dyck and Rubens and the demise of the great studio systems, became lost by the year 1700,” wrote Fels.24

Not only did nineteenth-century artists’ materials manufacturers, such as Reeves & Sons, Winsor & Newton, and Roberson, produce oil painting mediums to satisfy the hunger for the ‘lost’ mediums of the old masters, but they also innovated upon these mediums with variations based on developments in science.

Changes in Binding Media by Manufacturers in the Twentieth Century

Developments in the twentieth-century coatings industry enabled artists’ materials manufacturers to introduce new binding mediums for oil painters. Besides the traditional drying oils of linseed, poppy seed, and walnut oil, other drying and semi-drying oils are employed in modern oil paints, sometimes as cheap substitutes for traditional drying oils.

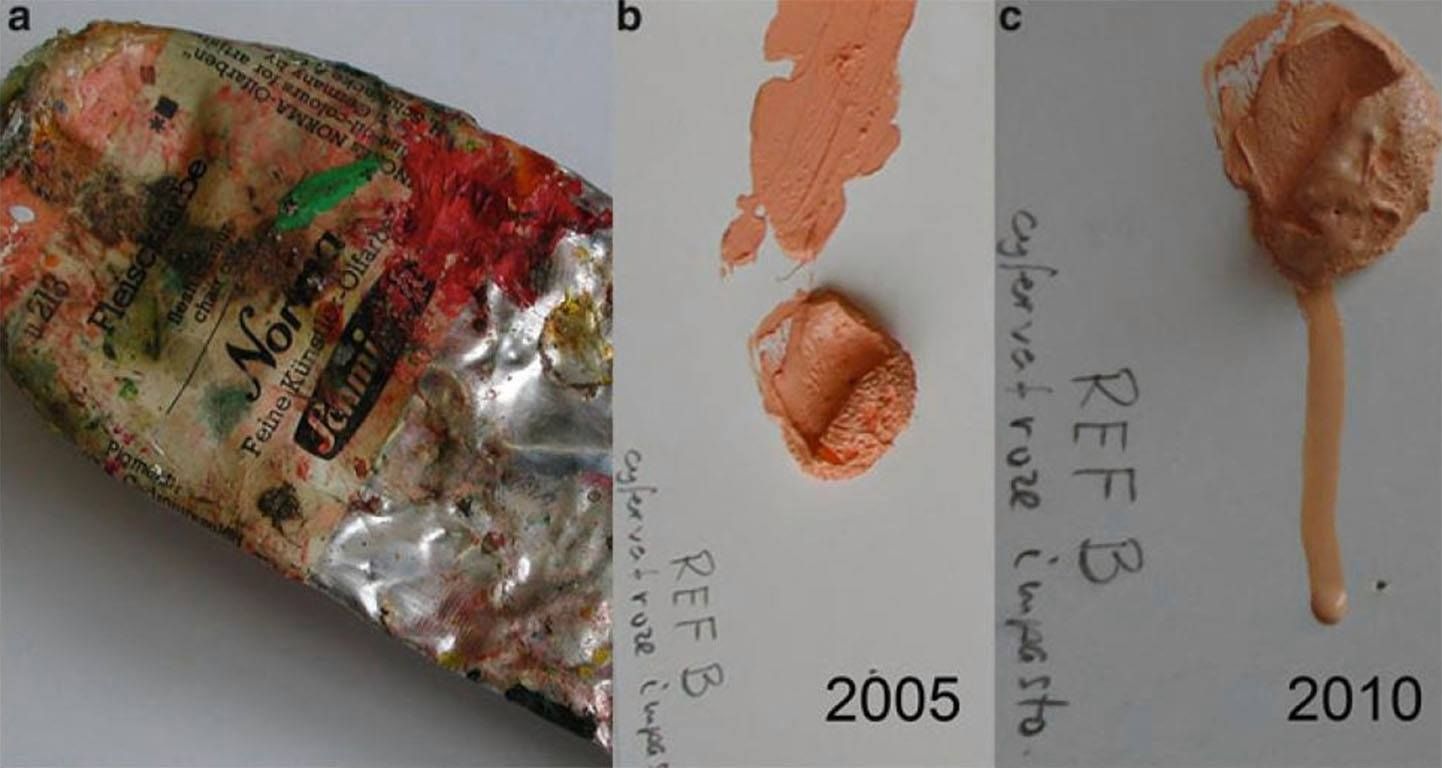

A tube of Norma Fleischfarbe pink paint (a) used by van Hemert for his Seven series paintings. The paint was used in 2002 for thin and thick paint application (b) on nonpermeable supports (Photos were taken in 2005 and 2010). In late 2009 the thicker impasto swatch (c) showed a molten appearance followed by drip formation (Boon 2014).

The use of these oils has not been without issues, causing defects never before seen in paintings of previous centuries. Although apparently dried, semi-drying oils applied in thick layers have been observed to ‘weep’ on modern oil paintings. Here an experiment with a cadmium hue in a mixture of sunflower-safflower oil weeps five years after the paint dried.25

Among the changes to modern oil paints have been the use of dispersing agents and stabilizers. The first to be used in modern oil formulations was aluminum stearate. This metal soap was first introduced in artists’ paints in the early twentieth century.26 Since that time, other agents have been used in modern oil paints, such as magnesium stearate, zinc stearate, and castor wax.27 28

The addition of stabilizers keeps the pigments in suspension, prevents oil and pigment separation, prolongs shelf life, and provides uniform handling properties of the paints in tubes. Although these additions to oil paints perform these functions well, they also reduce the cost of oil paint production since lower amounts of pigments are needed.

Many other additives have been included in oil formulations in modern manufacturing processes. Resins, fillers, surfactants, and other adulterants in different amounts are quite common especially for less expensive paints. Unfortunately, industrial secrets do not permit one to know about the addition of these materials, and labels on paint tubes are vague.

A phenomenon observed in modern paints not observed in paintings prior to the twentieth century is a milky haze on the surface of the paint film. After aging, superficial efflorescence is observed in modern paint films, particularly those with higher additives. This is likely the effect of the migration to the surface of additives, such as stearates and waxes.29

Paintings produced in the last 60–80 years generally suffer deterioration phenomena never or rarely observed in traditional oil paintings. In particular, twentieth-century oil paintings have conservation problems related to the fragility and sensitivity of the paint layers.

Conclusion

The binding media and technique employed by artists working in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries represent a dramatic change likely explained by the new social status of artists and the decline in the workshop tradition, creating the demand satisfied by industrialization and commercialization of artists’ materials. The loss of workshop tradition created uncertainty in materials and techniques, so an obsession developed to find the lost secrets of past masters. This obsession deepened the rift between the theory and practice of painting from the eighteenth century to the present day, causing the early failure of many paintings of this period.

Industrial development created new opportunities for painters and ultimately removed artists from the firsthand experience gained by making paint. The uncertainty in materials and techniques continued into the twentieth century, furthered by the commercialization of artists’ paints and the introduction of new binding materials by artists’ materials manufacturers based on scientific advances in the coatings industry.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the old masters' glazing technique?

Does anyone paint like the old masters today?

Yes, many contemporary artists study and employ the techniques of the old masters. These artists often blend traditional methods with modern perspectives and materials, aiming to preserve the craftsmanship and aesthetic qualities of historic art in their work.

Why are they called old masters?

The term "old masters" refers to European painters of high skill who worked before about 1800, or to the paintings themselves. It denotes artists who have mastered the techniques of their era and contributed significantly to the development of art in their and subsequent times.

Notes

1 Beal, Mary, A Study of Richard Symonds: His Italian Notebooks and Their Relevance to Seventeenth Century-Painting Techniques, Taylor & Francis, 1984, p. 74.

2 Williams, William, An Essay on the Mechanic of Oil Colours Considered under these heads: Oils, Varnishes and Pigments, Bath, 1787, p. 24.

4 Eastlake, Charles Lock, Materials for a History of Oil Painting, Vol. I, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1847, p. 405.

5 Little, Nina Fletcher, Neat and Tidy, New York: Dutton, 1980, p. 112.

6 Gower, Lord Ronald Sutherland, Sir Joshua Reynolds: His Life and Art, London: George Bell and Sons, 1902, p. 26.

7 Reynolds, Sir Joshua; Phillips, Lisle March, Fifteen discourses delivered in the Royal Academy, J.M. Dent & Co., 1906, p. 79.

8 Whittock, Nathaniel, The Decorative Painters’ and Glaziers’ Guide, London: Isaac Taylor Hinton, 1828, pp. 21–22.

9 Fairholt, Frederick, A Dictionary of Terms in Art, 1854, p. 222. ‘GUMPTION. Syn. Magilp.* This elegant and expressive name is applied to a nostrum much in request by painters in search of the supposed “lost medium” of the old masters, and to which they ascribe their unapproachable excellence. Notwithstanding the favour with which this compound is regarded, it has never been known to accomplish the desired object; nor can any rational mind be deceived into the delusion, that it was any such trifle as a medium that could impart those fruits which are due only to genius and well-directed industry. The old masters were not mere painters; they were, for the most part, men possessing highly cultivated minds, and truly devout; who would have achieved greatness in any other vocation. The formula for preparing this medium, gives a mixture of drying linseed oil and mastic varnish, which gelatinises; or simple linseed oil and sugar of lead.’ See Gumption, note, ‘Ingenuity appears to have exhausted itself in supplying names to this panacea for imbecility. In the different treatises on painting and in the colourmen’s catalogues we find it thus variously named. The list is too curious and significant to be omitted:—magelp, magelph, magilp, magylp, magylph, megilp, megelp, meirylp, megylph, macgelp, macgelph, macgilp, macgilph, macgylph, macgulp, magulp, megulph, mygelp, mygelph, muygilp, mygilph, myguip, mygulph, Gumption!’

10 Constant de Massoul, M., A treatise on the art of painting, and the composition of colours: containing instructions for all the various processes of painting. Together with observations on the qualities and ingredients of colours, Translated from the French, Published and sold by the author of the original, at his Manufactory. Printed by T. Baylis, 1797, pp. 24–25.

11 Morrison, Rachel, “Mastic and Megilp in Reynolds’s ‘Lord Heathfield of Gibraltar’: A Challenge for Conservation”, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, Vol. 31, 2010, pp. 112–128.

12 Whitley, William T., Artists and their Friends in England 1700–1799, Vol. 2, London and Boston, 1928, p. 282

13 Eastlake, Sir Charles Lock, Materials for a History of Oil Painting, Vol. 1, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1847, p. 265.

14 Eastlake, Sir Charles Lock, Materials for a History of Oil Painting, Vol. 2, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1869, p. 36. See note, ‘See the interesting account of Sheldrake’s experiments with amber and copal, Transactions of the Society of Arts, 1801, vol. xix. “These colours (mixed with amber) were not acted upon,” he observes, “by spirit of wine and spirit of turpentine united. They were washed with spirit of sal ammoniac and solutions of potash for a longer time than would destroy common oil-colours, without being injured.” The result of his experiments with copal was the same, “except that with copal the colours were something brighter than with amber.” He concludes:—“If my experiments have not misled me, I am entitled to draw the following conclusions from them:—Wherever a picture was found possessing evidently superior brilliancy of colour, independent of what is produced by the painter’s skill in colouring, that brilliancy is derived from the admixture of some resinous substance in the vehicle. If it does not yield on the application of spirit of turpentine and spirit of wine, separately or together, nor to such alkalies us are known to dissolve oils in the same time, it is to be presumed that vehicle contains amber or copal, because they are the only substances known to resist those menstrua.”’

15 Eastlake, Sir Charles Lock, Materials for a History of Oil Painting, Vol. 1, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1847, p. 275.

16 Eastlake, Sir Charles Lock, Materials for a History of Oil Painting, Vol. 2, London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1869, pp. 38–39.

17 Ruhemann, Helmut, The Cleaning of Paintings: Problems and Potentialities, New York: Praeger, 1968, see Appendix D, pp. 355–360.

18 Ibid., pp. 307–308, see also p. 237 note 1.

19 Maroger, Jacques, The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters, trans. E. Beckham, New York: Studio Publications, 1948.

20 Mayer, Ralph, The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques, ed., S. Sheehan, revised 5th edition, New York: Viking Press, 1991, p. 16. First edition, published 1940.

21 Mayer, Ralph, “The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters”, Book Review, Magazine of Art, Volumes 42–43, American Federation of Arts, p. 73.

22 Mayer, Ralph, The Painter’s Craft: An Introduction to Artists’ Methods and Materials, Third Edition, Viking Press, 1975.

23 Mayer, Ralph, The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques, ed., S. Sheehan, revised 5th edition, New York: Viking Press, 1991, p. 16.

24 “‘Lost Secrets’ of Painting Rediscovered”, American Artist, January 2004, p. 64.

25 Boon, Jaap J., F. G. Hoogland, “Investigating Fluidizing Dripping Pink Commercial Paint on Van Hemert’s Seven-Series Works from 1990–1995”, In: van den Berg K. et al. (eds.) Issues in Contemporary Oil Paint, 2014, Springer.

26 Tumosa, Charles S, “A Brief History of Aluminum Stearate as a Component of Paint”, WAAC Newsletter, Vol. 23 No. 3, September 2001, p. 1. Paper

27 Izzo, Francesca Caterina, 20th Century Artists’ Oil Paints: A Chemical-Physical Survey, Thesis, 2010, pp. 45–50. Paper

28 Fuster-López, Laura, Francesca Caterina Izzo, Marco Piovesan, Dolores J. Yusá-Marco, Laura Sperni, Elisabetta Zendri, “Study of the Chemical Composition and The Mechanical Behaviour of 20th Century Commercial Artists’ Oil Paints Containing Manganese-Based Pigments”, Microchemical Journal 124, 2016, p. 966. Paper

29 Schilling, Michael R., David M. Carson and Herant P. Khanjian, “Gas Chromatographic Determination of the Fatty Acid and Glycerol content of Lipids. IV. Evaporation of Fatty Acids and the Formation of Ghost Images by Framed Oil Paintings”, In Proceedings of the 12th Triennial ICOM-CC Meeting, Lyon, 29 August-3 September 1999, Vol. I, pp. 242–247.